Book Review: Collective Processes – Guest Critic Mimma Tuomisalo 04.07.2022 – Posted in: Book Thoughts

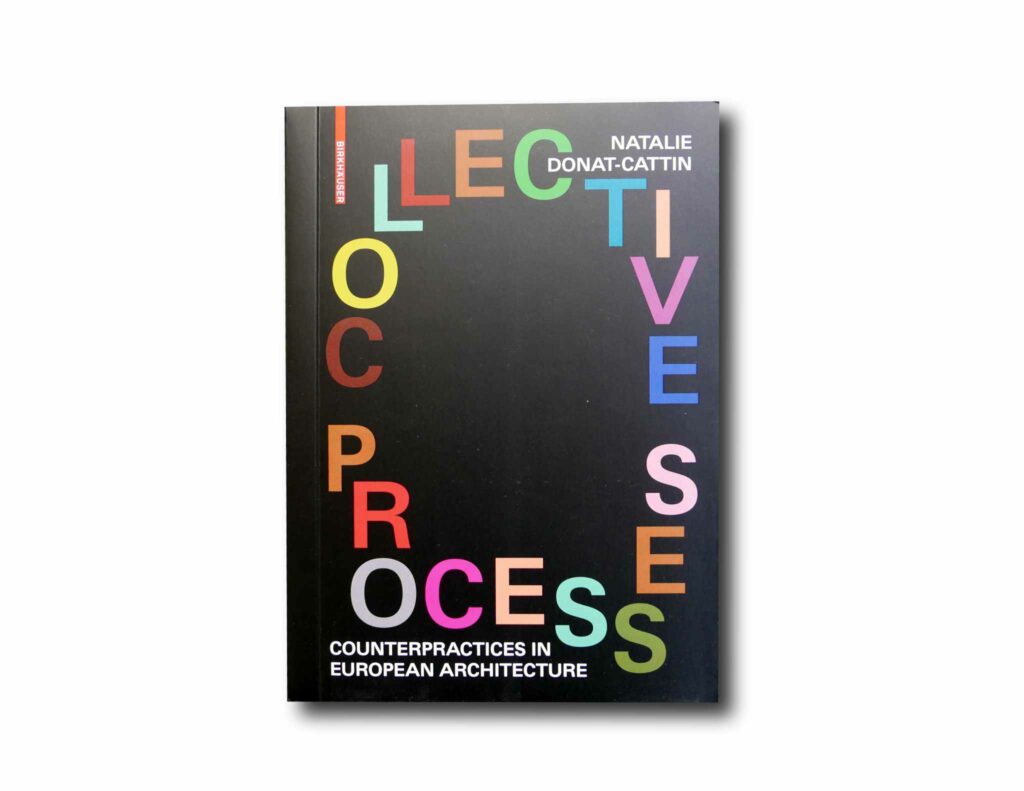

Books are meaningless without readers. This blog post continues our little series that features interesting new titles viewed through a lens of a critical reader. This time, our guest critic is Mimma Tuomisalo who reviews Natalie Donat-Cattin’s Collective Processes – Counterpractices in European Architecture published by Birkhäuser ealier this year. Please also take a look at Pijatta Heinonen’s review of Architects after Architecture – Alternative Pathways for Practice.

Text by Mimma Tuomisalo (b. 1994) who explores settling in the world from the juxtaposition of her two educations. She is both a master student of architecture at Aalto University and master student of time and space arts at the University of the Arts Helsinki. The most recent themes of her work are the production of the built environment and its consequences, gendered spaces and tasks, the ambiguity of work and nostalgia.

Featured image: Untold stories, discussion, Habitabis Festival, Lisbon, 2018©COLECTIVO WAREHOUSE.

Collective Processes

Natalie Donat-Cattin is a researcher and practicing architect, whose work at the École Polytechnique de Lausanne focuses on contemporary forms of horizontal organisations in architecture, such as the collective. Collective Processes – Counterpractices in European Architecture (Birkhäuser, 2022) collects together discussions held during 2019 and 2020 between 17 collective architectural practices from Europe that depict their roots, dynamics and work. The book is beautifully fragmented: It presents light analyses on questions of the architecture work culture, but focuses on transcribed conversations held between different collective actors. The book contemplates the possibility of changing the architectural process and the approach of the discipline itself.

Book as a conversation

The form of transcribed discussion is wonderful. The feature of conversation that is inherently meandering comes through in text form and allows the reader to get engaged. The reader feels like taking part in an interesting exchange but is able to go back and choose in which ideas to linger longer. The urge to scribble the marginals full of your own thoughts, responses and exclamation marks is alluring.

On the other hand, the conversational form doesn’t follow a structure that eventually would give an answer to a given subject. A topic like collective working could also be approached in a more explanatory way, but the book’s conversational form allows many solutions and ideas to coexist. The reading experience is more like being able to witness someone’s take on a subject and someone else’s response to that without producing answers applicable on the general scale. The discussions offer some experiences that have been made in the field of collective working in architecture for the reader to reflect on.

How do we practice and why do we practice?

The structure of the book brilliantly supports the chosen conversational form. When presenting architectural practices it is seldom mentioned how they function. Many architecture publications focus on the product rather than the process. In this case the introduction of the collectives’ work comes only in the end, rather late, especially when talking about alternative practices. First Donat-Cattlin introduces the context and frames the subject by briefly addressing some questions on authoriality in the history of architecture and the socio-ideological context of Europe, and elaborates on the ways of working have changed during the last 30 years and how the new technological possibilities have reshaped our ways to organize.

After the introduction of the topic comes the main conversation, a roundtable discussion between (ab)Normal, A-A Collective, Assemble, baukuh, CNCRT, Colectivo Warehouse, Collectif Etc, constructLab, false mirror office, Fosbury architecture, la-clique, Lacol, n’UNDO, orizzontale, raumlabor, X=(T=E=N) and Zuloark. The conversation allows the participants to discuss their particular experiences and responses to common problems that the field of architecture embodies.

In a later stage the groups are asked on how they have gotten together and why, what their working spaces are like, how the collective is structured, how it has changed since their inception and what is the key aim of their architecture. Interview-like starting points morph into discussion by every participant’s different way of outlining the questions. The answers are variations of a similar situation with diverse solutions and allows the reader to reflect on the differences between the groups.

“Architecture is a collective process, a common practice. This dimension is never recognized by contemporary institutions of work, whether it is office, university or collective”, addresses Luciano Aletta from CNCRT (p.31). Architects are inherently in a position of power when creating architecture and proposing a new alternative way to organise a working community is never a direct solution that would change the power dynamic. Many of the collectives, some of which have chosen to not to even use the word collective, talk openly about their active struggle to find ways to incorporate their values in their practices and explain how they have been changing throughout the years trying to find a solution.

Creating complex human environment

Mainstream architectural practice still mainly exists in a small economical niche where the construction industry dictates the rules. In this space also the narrow ideas of success and starchitects are usually very much alive, even if we tend to think that it would be something we have already dealt collectively with, because both of them are further boosted by the individualistic capitalistic culture we live in. Natalie Donat-Cattin opens the roundtable discussion between collectives by a quote from Brussels: A Manifesto towards Capital of Europe:

“[T]o realize built architecture, architects have to explicitly or implicitly, consciously or unconsciously, comply with the priorities of the power system in force. Architects whose principles oppose these priorities find themselves unable to realize their architecture and can only postulate, by means of projects, conjectures anticipating an alternative regime. Often they are harbingers of the regime.”

Aureli, Patteeuw, Deklerck & Tattara: Brussels: A Manifesto towards Capital of Europe (Rotterdam, NAi Publishers, 2007), p.7

In order to create a complex human environment, the aims, ways and practices for creating should be as diverse as the result we want to achieve. The majority of the environment created under the current power structure is extremely homogenous. Collective implies a strong relational bond between members based on friendship and fairness. The core idea is to share: share materials, work, space, benefits and risks. The fear of a betrayal of one’s principles, and the compromises one has to make instead of bargaining their ethics, is also easier to bear when the burden is shared.

Text by Mimma Tuomisalo. Published by Bookmarchitecture Oy by permission of the author.

Would you be interested in reviewing architecture books for our shop blog? Give us a shout, we’d love let our audience hear your voice on this platform. /// Kiinnostaisiko sinua arvioida uusia arkkitehtuurikirjoja blogissamme? Ota yhteyttä, olisi mahtavaa saada äänesi yleisömme kuuluviin tällä alustalla.