Utzonia: From/To Denmark with Love 06.01.2022 – Posted in: Book Thoughts

Jørn Utzon (1918–2008) is undoubtably one of the heroes in Nordic modern architecture. The Danish architect was awarded with the the precious Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2003, and his best known work is the iconic Sydney Opera House (1959–1973) – a building, according to UNESCO, with outstanding universal value and a masterpiece of 20th-century architecture for its unparalleled design and construction. A new book – Utzonia: From/To Denmark with Love – gives a critical look towards fourteen buildings and building complexes designed by Utzon. I had an email chat with the editors Angela Gigliotti and Troels Rugbjerg about the intentions of this highly intriguing publication.

Your book is both a contribution to the existing knowledge of Jørn Utzon’s legacy and an experiment in architectural pedagogy at Aarhus School of Architecture and at DIS Copenhagen, Denmark. How would you summarize the relationship between 21st-century undergraduates and the 20th-century modern masters such as Utzon? What kind of relevance can “learning from a master” pedagogy have to contemporary students?

AG: If we have to find an adjective for summarizing such a relationship we will go for disruptive! We live in a very peculiar moment in academia in which we are asked to disrupt the way in which so far, we have been trained as architects in order to include a more sensible social responsibility of architectural discipline as a science towards urgent topics (labor, gender, race, and climate to mention the first four that pop up in my mind). What was a stake in our courses was the production of a collective outcome in which students deserved to be “cited” for their efforts in the knowledge production. The relationship between masters of the 20th century and contemporary students is disruptive because we wanted to decolonize a dominant idea of the architectural master as someone with a sense of superiority that hardly can be criticized. On the opposite, the students were asked to draw and create models that correspond to their own interpretations of architecture being developed by someone else.

It was an experiment, a very free approach that the students really appreciated. So, being more precise, all the drawings were made by students enrolled at DIS while all the models by students enrolled at AAA. And that’s how we experimented and found one possible alternative to a way of teaching and education of the “old schools” of architecture. We don’t want to impose any positions on others, we don’t have any gospel to preach them…it is up to the students to develop their own critical perspectives and learn from what the course and our experience might offer. We strive to create a framework where students can grow as critical thinkers first of all.

Your introduction frames Utzon’s architecture as an important contributor to the Danish welfare society, but you also give recognition to recent research of its international influences such as Chinese, Arabic and middle Eastern architecture. Was this flux of international and domestic cultural impacts – import and export – unique to Utzon, or would you rather regard it as a constituent of architectural modernism in general?

TR: Yes, the International aspect of architectural modernism is definitely important in general, and in the case of Utzon’s work of architecture this was especially important. One aspect was a postcolonial situation where wealthy nations as e.g. Denmark was providing “hard aid” after World War II to erect new constructions from the use of new building techniques involving prefab concrete elements. This would however develop into the export of a “softer aid” of values and culture coming from the Danish welfare society. Utzon contributed to this development. Being at the same time deeply related to a specific site Utzon’s architecture can be seen as distinctive in its ability of being quite locally related for a place and at the same time incorporating ideas of foreign cultures and/or introducing new modes of construction techniques having an international character. Utzon developed an understanding about different cultures and ideas of building through an immense curiosity – “Importing” this knowledge provided him with abilities for letting these visions be transformed in to new architecture elsewhere – to “export” them.

This situation of import and export did, however, also happen within political contexts that Utzon would seek to manoeuvre in, which also proved to be difficult. In the case of the Sydney Opera House, his visions for a new architecture ended up being part of a larger political quarrel. In the case of the Kuwait National Assembly, one might identify how a vision of democracy was being exported through spatial effects made for informal meetings between people and the possibility for having a debate. In the end, however, this building project was and cannot guarantee that values of equality, free dialogue and such are incorporated, even though the design might allow for this to happen.

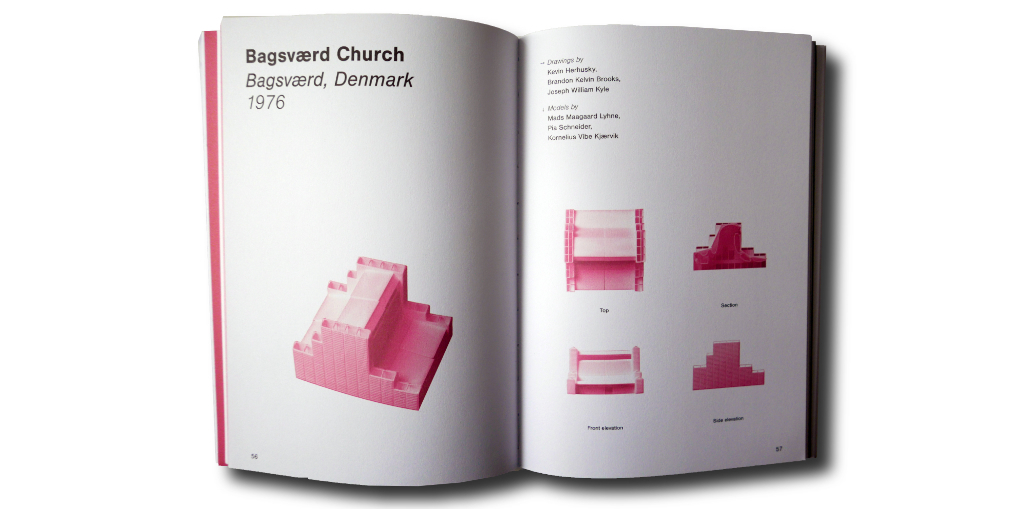

The students’ reproductions such as physical models, split 3D-models, and drawings compose one of the most visually striking features of the Utzonia book. The abstract monochromes on red or green look very different from what is conventionally used in architecture books, and you have also omitted all original or archival material. Can you tell a bit more about the benefits of this technical and visual approach to critical re-interpretation – given that your coursework also entailed reading critical texts about welfare architecture and its political and ideological meanings? Has this something to do with the “technical and cultural x-rays to a project” that Fabio Gigone talks about in the concluding interview on his Instructions and Manuals column in Abitare 2008?

AG: Definitely, we asked the students to find their own means of knowledge production departing from what was offered by us and going beyond that. Some of the sources used by the students were more conventional than others covering what Gigone addressed as technical and cultural realms. Students developed original drawings and theoretical critical texts, but also real estate advertisements, post-occupancy studies, instagram feeds, trip reports… After weeks of navigation online and offline and having created a sort of knowledge atmospheric cloud around them, they were asked to condense all of that into a single given layout able to communicate both an own interpretation of such architectural built projects using only three elements: data, captions and vectors; and, a collective outcome across several semesters of the same class.

Lastly, your write that the title Utzonia refers to an imaginary setting for a city. How would you describe Utzonia? A commodification of Nordic living; the last resort of the Modernist utopia; the monument for long lost idealism; or what?

TR: Maybe this imaginative idea of an Utzonian city could be described as all of these three statements? Utzon’s architecture does, on one hand, relate directly to different influences and contexts such as cultures of living and techniques of construction. On the other hand, his architecture often stands out also as distinct works of art that might even seem rather closed – where Utzon is often quite occupied with designing interior space that would leave less focus on the exterior. In the case of the Melli Bank in Tehran, he does, howeve,r create a distinct intermediate space that is a smaller square between a buzzling city and to the building and the simple façade it reveals to the city. In his first design for the Kuwait National Assembly, he demonstrates distinct ideas of developing this huge building complex from a principle of an organic city development that could grow and was possibly everchanging – something which unfortunately was not realized in the actual construction.

With this book we imagined what it would be like if Utzon had been responsible for a larger project development, with several different functions and maybe developed it over a longer period? An Utzonia that could possibly be described by the all of the three statements of your question; however, Utzonia might also be described as organic and in a close relation to nature, involving principles of growth and change that he envisioned for the Kuwait National Assembly, while at the same to presenting itself with a distinctive coherent appearance.